Ancient Africa – Civilization, Religion, Rituals & Culture

Published on: 17-Feb-2025

, Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 936-968.)>undefined

, Seerat Research Center, Karachi, Pakistan, Vol. 2, Pg. 936-968.)>Africa has been a bewildering blend of different and overlapping societies and cultures. As the second largest continent in the world, it comprised of various civilizations and nearly every one of these civilizations contained separate and overlapping local societies, cultures, and languages. Ancient Africa was home to the Egyptian, Roman, Nigerian, Abyssinian and various ancient civilizations.

The writings of the ancient Greeks and the Egyptians record that there was an advanced culture in Ethiopia from around the 3rd millennium B.C. Recorded history in Ethiopia begins with the influential D’mt Kingdom, 1 D’mt flourished between the 10th and 5th centuries B.C. from its capital at Yeha but not much is known about the culture. Sabean influence was evident in the temple to the moon-god Almaqah, the most powerful Sabean deity, which still stands. Scholars are divided on how much the Sabeans influenced the culture of D’mt but the existence of the temple and linguistic similarities indicate a significant Sabean presence in it. 2 This kingdom was followed by a period in which petty kingdoms vied for power until the emergence of the Aksumite Kingdom in the 1st century A.D. The Aksumite Kingdom was the precursor of an Ethiopian Empire than persisted for almost 2,000 years until the last Ethiopian emperor, Haile Selassie-I. 3

Geography

Africa is the second largest continents on Earth spanning around 11.7 million square miles. On the north, where it shared the waters of the Mediterranean Sea with Spain, Italy, and Greece, it lies close to Europe. Only the narrow Red Sea separates it from the Middle East. Its western shore stretched along the North and South Atlantic Ocean, and its eastern shore up to the entire length of the Indian Ocean. Because of its vast size Africa was a land of contrasts. It contained one of the world’s greatest deserts, the Sahara, which stretched across the north-central part of the continent, dividing north from south. North of the Sahara lay countries rich with ancient tradition. 4 Ethiopia was the name given to the countries inhabited by black or tawny people. There was Nubia and Abyssinia in the upper part, and Congo, Lower Guinea, and Caffraria, in the lower; but as these countries have never been united, the kingdom of Ethiopia, as mentioned in the Scriptures, and referred to by ancient historians, was comprised in Nubia and Abyssinia. 5 Africa Propria, or the province of Africa, properly so called, lay along that part of the coast which led from north to south. The bay formed by the southern part of this land was the Syrtis Minor, a dangerous quicksand; and in that formed by another sweep of the sea, after which the coast took again a north-easterly direction, was the Syrtis Major. Between the two Syrtes was Tripolis, now Tripoli. To the east of Africa lay Numidia, now Algiers. The city of Utica, upon this coast, was memorable as giving name to Cato Minor, who, disgusted with the loss of liberty in Rome, here destroyed himself. Utica, like Carthage, was a Tyrian colony, and founded the first, but did not attain distinction till after the downfall of its rival. 6

Climate

From around ten thousand years ago to about 3 000 B.C., the continent experienced a long humid phase. This period was significant for the development of the Sahara. At the time, lakes were at a much higher level than they are today, and the forests were at their maximum extension. But during the second and especially the first millennia B.C., the climate progressively dried; swamps and forests receded; and grasslands flourished. The change was due to both less rain and to human activity. Sometime around the dawn of the Christian era, between fifteen hundred and two thousand years ago, this biogeographic change accelerated: land clearing led to forest recession and to more open spaces - a change that undoubtedly was connected to keeping farmland fallow for long periods, to herding, and to wood - cutting for blacksmithing and charcoal burning. 7

Religious Beliefs

African religion had no single founder or central historical figure. Although traditional African religion varied widely from region to region and people to people, there were a number of things that they all had in common. All things in the universe were part of a whole. There was no sharp distinction between the sacred and the non-sacred. In most African traditions, there was a Supreme Being: a creator, sustainer, provider, and controller of all creation. Serving with the creator were a variety of lesser and intermediary gods and guardian spirits. These lesser gods were constantly involved in human affairs. People communicated with these gods through rituals, sacrifices, and prayers. They believed that the human condition was imperfect and always will be that way. Sickness, suffering, and death were all fundamental parts of life. Suffering was believed to be caused by sins and misdeeds that offend the gods and ancestors, or by being out of harmony with society. Ritual actions were believed to relieve the problems and sufferings of human life, either by satisfying the offended gods or by resolving social conflicts. Rituals were thought to help the people in restoring their traditional values. Ancestors, the living, the living-dead, and those yet to be born were all an important part of the community. The relationships between the worldly and the otherworldly helped to guide and balance the lives of the community. Humans needed to interact with the spirit world, which was all around them. 8

Concept of God

Africans believed in ‘high god’ who created the universe. This god was distant and unconcerned with daily life. 9 African people whose cultures were organized as monarchies with a king at the head usually believed that God as a supreme king. As there was only one supreme king in a community, Africans traditionally concluded that there was one Supreme Being for the entire human race. The majority of African peoples conceived of God as one. 10

Both African oral traditions and later written sources indicate that all African peoples believed that power of creation was the foremost attribute of the Supreme Being. African myths of creation strongly support the idea that all Africans at all times from prehistory to the present-day have recognized a Supreme Being as the Creator of all things. In addition, the names by which many different groups across Africa call the Supreme Being express the idea of God as the ‘Originator,’ Creator of everything. 11

In Africism, God was the Supreme Being. This supremacy was recognized through the numerous African primary sources that, from time immemorial, had consistently been handed down, in African folklore, from generation to generation. This one God was known by many names, according to the cultural peculiarities of African peoples. The many names by which Africans expressed themselves about the uniquely one Supreme Being did not, in any way, turn their understanding of the Supreme Being into many Supreme Beings. Here the concept of the Supreme Being enjoyed the unity of essence, on the one hand, while it entertains the diversity of the manifestations of the names, on the other hand. By unity, the Supreme Being was expressive of Monotheism in the religious and thought system of Africa. 12

In Africa, religious systems were usually classified as either monotheistic or polytheistic. In African religion monotheism and polytheism existed side by side. Often the African concept of monotheism was one of a hierarchy with a Supreme Being at its head. In this system the Supreme Being ruled over a vast number of divinities who are considered to be the associates of the God. African understanding of the structure of the heavenly kingdom might be compared to the Christian concept of God ruling over the saints and angels. The divine hierarchy in African religion made it possible to classify them as both monotheistic and polytheistic at once (monotheism with polytheism) 13 which was definitely and self-contradictory.

Superhuman Beings

The Africans also believed in the superhuman beings and they had a more direct impact on human life. These superhuman beings were called gods and spirits. They also included the souls of dead. 14 Superhuman beings were spiritual inhabitants of the spirit world. Some of them were deities and/or secondary gods, others were specified as ancestors. Spirits of the departed inspired a sense of super humanity. For that reason, the presumption in Africism was to handle the spirits of the departed with care. Among some Africans, superhuman beings were recognized as ancestors. Among other groups, spiritual entities were specifically and honorifically grouped in pantheons. Some have argued that Africism was polytheistic because of the existence and veneration of lesser divinities and ancestral spirits. Africism was more correctly understood as henotheism, that is, the acceptance of the existence of secondary deities and lesser spirits, without being distracted away from monotheism, that is, the idea of a Supreme Being. 15

Berber Religion

The region in northwestern Africa is believed to have been inhabited by Berbers from at least 10,000 BC. 16 In ancient history, the Berber individuals followed to the customary Berber religion, before the arrival of Abrahamic beliefs into North Africa. This customary religion intensely underlined predecessor worship, polytheism and animism. Numerous old Berber convictions were grown locally, though others were impacted after some time through contact with other conventional African religions like the Ancient Egyptian religion, or acquired amid relic from the Punic religion, Judaism, Iberian folklore, and the Hellenistic religion.

Kushite religion

Kush was the name given in ancient times to the area of northeast Africa lying just to the south of Egypt. It is the Ethiopia of Herodotus and other classical writers, and it corresponds in a general way to the Nubia of today. Its peoples were and are African in race and language, but since very early times their culture has been strongly influenced by that of their northern neighbors.

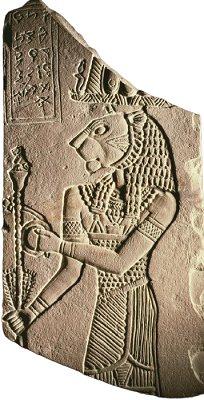

In the Meroitic period (350 B.C.–350 A.D.) the Kushite pantheon came to include a number of deities who were apparently not of Egyptian origin. The most important of them was Apedemak, a lion-headed male god who was a special tutelary of the ruling family. He was a god of victory and also of agricultural fertility. There were temples of Apedemak at Meroe and at several other towns in the southern part of Kush, but his cult seems to have been little developed in the more northerly districts, which were far from the seats of royal authority. Two other possibly indigenous deities were Arensnuphis and Sebiumeker, who are sometimes depicted as guardians standing on either side of temple doors. There was, in addition, an enigmatic goddess with distinctly negroid features, whose name has not been recovered till date. Cult animals were evidently important in Kushite religion. Cattle are often depicted in temple procession scenes, and at the southern city of Musawwarat there was apparently a special cult of the elephant. 17

Aksumite Religion

Aksum was an old kingdom situated in what is currently in northern Ethiopia and Eritrea. 18 Akumite Emperors were powerful sovereigns, styling themselves King of kings, king of Aksum, Himyar, Raydan, Saba, Salhen, Tsiyamo, Beja and of Kush. 19

The Aksumites followed a polytheistic religion identified with the religion rehearsed in southern Arabia. This incorporated the utilization of the crescent-and-disc image utilized in southern Arabia and the northern horn. 20 Francis Anfray, recommends that the agnostic Aksumites worshipped Astar, his child, Mahrem, and Beher. Steve Kaplan contends that with Aksumite culture, came a noteworthy change in religion, with just Astar remaining of the old gods, the others being replaced by what he calls a triad of indigenous divinities, Mahrem, Beher and Medr. He likewise recommends that Aksum culture was fundamentally affected by Judaism, saying that the primary transporters of Judaism achieved Ethiopia between the rule of Queen of Sheba B.C. 21 and transformation to Christianity of King Ezana in the 4th century A.D.

Christianity in Africa

Historians believe that Christianity first came into Africa around 40 A.D. through Alexandria, a city of the Hellenic Empire founded by Alexander the Great. At about the same time a Christian community arose in Egypt that was made up of native Egyptians. The Copts, a Christian tradition, trace their origins to the preaching of Saint Mark, one of the writers of the Christian Gospels, who visited Egypt. Another way through which Christianity spread to Africans was through Carthage, a Roman province that lay in what is now Tunisia. From about 44 A.D. Carthage was culturally Roman; its official language was Latin. The official religion was worship of the Roman gods. Christians were persecuted and even killed. Persecution seems to have worked against the Romans, however, because Christianity grew rapidly in North Africa. African Christianity produced such great leaders as Tertullian, Saint Augustine, Saint Cyprian, and Saints Perpetua. At least one writer, Tertullian, recognized the importance of the African religious concepts of God to developing Christianity. In 350 A.D., the ancient kingdom of Aksum, known as Ethiopia today, officially embraced Christianity. At that time the Aksumite king Ezana, originally a strong adherent of his African religion, converted to Christianity. Aksumite Christianity, later called Ethiopian Christianity, has its roots in the Coptic Christianity of Egypt. 22

Aloysius M. Lugira provided a long list of other African religions which were existing in different parts of Africa at that time including: Dinka Religion, Nuer Religion, Shilluk Religion, Galla Religion, Acholi Religion, Ateso Religion, Baganda Religion, Bagisu Religion, Banyankore Religion, Langi Religion, Banyoro Religion etc. 23 which were hundreds in number and had different gods and beliefs but later on, they became Christians before the Advent of Prophet Muhammad ﷺ and several converted in Islam when it was propagated. But still there are multiple religions which are surviving at its different parts.

Burial Rituals and Tombs

Africa provides evidence of some of the world’s oldest burials and mortuary rituals. At a site containing some of the oldest human remains, near Herto, Ethiopia, the skull of a child from 160,000 years ago was found to be so polished that it must have been repeatedly handled, probably in a ritual-like way. Ocher (a powdery form of iron-rich earth or clay that can be used as a pigment) and other materials such as shells have served as mortuary goods and for other ceremonial purposes for thousands of years in much of Africa, continuing up into contemporary times. Red ocher is of great ritual significance both in life and in death. During the 4th and 5th century B.C. in Aksum, a city and kingdom in highland Ethiopia, gravesites of rulers were marked with some of the world’s tallest obelisks, monolithic pillars up to 100 feet high. During this time the practice of erecting obelisks and granite tombs for leaders held sway in numerous settlements extending from the Ethiopian highlands to the Red Sea coast. Cremation was another possible way of dealing with the dead, and there is early evidence of this practice in Africa. For example, along the Rift Valley in western Kenya the famous archaeologists Mary and Louis Leakey excavated a Late Stone Age cave site known as the Njoro River Cave that dates to around 1200 B.C. There a number of cremated remains as well as funeral offerings that had also been partially burned, including elaborately decorated wooden vessels, baskets, beads, shells, and semiprecious stones that were probably strung together and worn as jewelry were found. Throughout Africa the burial of the dead was a community matter, and there was great concern with honoring and maintaining a proper relationship with the spirit of one’s ancestors. 24

Only very few Iron Age burials are known. Several assemblages of intact vessels that came to light in Libreville have been interpreted as grave deposits. At Mbiala Cave in the savannas of the Niari river valley (southern Congo), an ossuary with three heaps of human crania and bones were found. Two of the crania were of young females, all mandibulae missing. The bones had been intentionally broken and laid down without any anatomical order. A small iron rod and a presumed iron lance or arrowhead lay close to the major bone concentration. No interpretation has been offered for this complex, dated to 1310 B.C. A small number of inhumation burials in simple earth pits dug between and underneath houses are known from a fishing camp site on the Tshuapa River in the interior Congo basin. The deceased had been buried lying on their sides in an extended or flexed position. In several instances, bones of one infant and one adult individual were found together in the same grave. A baby burial contained an iron arm ring and a necklace of carnivore teeth. A red substance, possibly pigment, was found underneath the pelvis of a woman who had died in pregnancy. Only one of these graves could be dated to around 660 B.C. A secondary, partial burial of one small-statured individual was unearthed at the site of Maluba on the Lua River, in the northwestern corner of the Congo basin. A possibly ritual deposit made up of a ceramic vessel and an iron ring was unearthed in a Late Iron Age iron furnace in Teke land (Congo). ‘Domestic’ pits in Southern Cameroon and Gabon frequently contain conspicuously large quantities of ceramics, including complete or nearly complete vessels, polished stone tools or fragments thereof, grinding stones, charred oil palm nuts, endocarps of Canarium schweinfurthii, and charcoals. Such inventories might reflect purposive selections rather than contingent refuse assemblages and could possibly be interpreted as intentional pottery depositions like those known to have been laid down in the inner Congo Basin from 2300-650 B.C., perhaps in the context of mortuary practices, ancestor worship or both. 25

The dead were buried on the spot, with no goods in their graves. The body lay in various positions. 26 The Grave found in the Bantu era, showed the burial practices. The dead wore many ornaments, bracelets, rings, neckless, pendants, strings of beads and shells, cowries, conuses and beads of glass or stone may have served, among other things, as coin in the same manner as the small crosses. 27

Many large, stone-built surface tombs in North Africa were found in northern Europe, which seem to be from 1st millennium B.C. Large structures in Algeria such as the tumulus at Mzora (177 feet (54 metres) in diameter) and the mausoleum known as the Medracen (131 feet (40 meters) in diameter) were probably from the 4th and 3rd centuries B.C. and show Phoenician influence, though there is much that appears to be purely Libyan. 28

Human Sacrifices

Human sacrifice was the element in Carthaginian religion. It persisted in Africa much longer than in Phoenicia, around into the 3rd century B.C. The child victims were sacrificed to Baal and the burned bones buried in urns under stone markers, or stelae. At Carthage, thousands of such urns have been found in the Sanctuary of Tanit, and similar burials have been discovered at Hadrumetum, Cirta (Constantine, Alg.), Motya, Caralis (modern Cagliari, Italy), Nora, and Sulcis. Carthaginian religion appears to have taught that human beings were weak in the face of the overwhelming and capricious power of the gods. 29

Social Structure

Not much is known about the African tribal cultures, since there is no recorded evidence. The first humans on the African continent lived in bands, small groups of related people with informal leadership. Bands did not have laws, and customs were transmitted orally. Most bands were hunter gatherers, people who moved from place to place following the animals they hunted. These were usually two social classes, elite and commoner, and each individual was born into a particular class. Power was centralized and leaders tended to be male. The chief, who would be male, inherited through the mother’s line. 30

Calendar

While ancient Africans in general had little interest in measuring the hours and minutes of the day, they needed to mark the passage of the seasons. 31 Archaeologists believed that the Ancient Africans were the first people in the world to create calendars and make calculations. A baboon bone found near South Africa was the oldest and had notches or represented numbers. 32 Recent archaeological discovery was a piece of bone found in the present-day Republic of the Congo. Dating back to between 9000 and 6500 B.C., the bone had 39 notches carved on its surface. At first, the artifact was believed to be linked to some kind of numerical notation. Further study, however, led scholars to suggest that the notches are part of a system noting the phases of the Moon. 33

The ancient Africans developed an expertise in astronomy, for the progression of days, months, seasons, and years represents the movement and rotation of the earth in relation to the sun and moon. One of their major findings was the discovery of a calendar system used by the Borana of southern Ethiopia and northwest Kenya. The Borana, ignoring the sun, developed a calendar regulated by seven stars and star groups observed in conjunction with the phases of the moon. Recently, archaeologists discovered at a site near Lake Turkana in Kenya a cluster of 19 stone pillars. The name of the site was Namoratunga, meaning ‘stone people.’ Writing carved on the stones provided evidence that the pillars date to 300 B.C. The Borana measured time using a 354-day lunar year with 12 months; they did not keep track of weeks. Every three years a leap month was added so that the lunar years remained consistent with the 365-day solar year. The Borana relied on seven stars or star groups: Their modern names are Triangulum, Pleiades, Aldebaran, Bellatrix, Orion’s Belt, Saiph, and Sirius. The New Year began when a new moon was observed in conjunction with Triangulum; the next month began when the new moon was seen in conjunction with the Pleiades, and so on. The Borana had names for only 27 days of the month, even though the month could be as long as 30 days; when they arrived at the end of the list after 27 days, they started over with the name at the beginning of the list. 34 Other people dealt with the discrepancy between the lunar and solar cycles by creating twelve different months that were, in turn, divided into four unequal weeks. Thus, a month would begin with the disappearance of the moon and then progress through weeks lasting for 10 days, four days, and five days. Each of these days often had a particular spiritual significance and was believed to bring either good or bad fortune to humans, domesticated animals, and wild creatures alike. Some people developed particularly accurate systems for predicting the seasons. The Kamba of present-day Kenya, for example, traditionally calculated the arrival of rainy and dry seasons with the aid of the sun. By drawing lines through certain points in their fields, they were able to measure the position of the sun and make surprisingly accurate predictions about the arrival of the seasons. 35

Family

The typical African family in ancient times was both a social/cultural and production unit. It was a social unit because all individuals belonged to a family, which served as a vehicle for socialization and cultural assimilation. The family therefore integrated people into the culture of the entire community. As a production unit, all members of a family were collectively involved in tilling the land and producing agricultural products. The most prevalent type of family in ancient Africa was the extended family. An extended family consists of numerous families that descend from a single ancestor. Most extended families, often made up of several generations, lived in compounds, with different huts belonging to individual families. Among the Yoruba of southwestern Nigeria, some families were exclusively responsible for producing the king because the oral history of the community indicates that their forefathers were responsible for establishing the community and laying the foundation of its culture and tradition. All families were traditionally headed by the oldest male, because most African societies were patrilineal. Also, ancient African societies were predominantly gerontocratic, meaning that the oldest men and women were expected to guide and lead the community because of their wealth of wisdom, which came with age. Again, among the Yoruba the oldest man who looked after the day-to-day activities of the extended family was called the Oloriebi, or ‘the head of the family.’ Not all families derived means of survival and livelihood from agriculture. Some were artisans such as wood carvers and blacksmiths. Some were entertainers, while others were diviners and healers. The skills required in these professions were transmitted from one generation to another. The endogamous nature of African families, where marriage took place within the tribe or clan, ensured that skills were passed from one generation to another within the family and was a significant factor in the survival and resilience of most ancient crafts. Aristocratic families had slaves as members. In most cases, these slaves were bought and integrated into the family for the purpose of agricultural production. Theoretically, slave owners had the power to kill or sacrifice them to the gods. Marriage with the master would free the female slave and her children from slavery. 36

The family unit consisted of a man, his wife or wives and their children. The family group added those related by blood, including, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. The father’s position in the community depended largely on the type of homestead he kept and how he managed it. Good management implied he was able to manage public affairs. When there was more than one wife, the mother was the immediate head of the family set, her hut, her children, her personal ornaments and household utensils, the crops of her cultivated field and granaries (places where grain were stored). The relation between wives were that of partnership. The head wife had no superior authority over the rest but was respected for seniority, in age, provided she deserved it. Her main official duty in the homestead was to take a leading part in the religious and other ceremonies performed in the interest of the family group. Good breeding and custom dictated that relatives help and consult one another in matters of common concern. All members of a family members were reared to stick together. 37

Architecture

African culture, material and climate shaped its architecture. When interior Africans settled in the Valley of Nile, they utilized the stones abundantly present in the cliffs. Prior to that time structures were made of sunbaked brick reinforced with the reed of the papyrus and lotus that grew plentifully on the river’s banks. 38

Most ancient Africans used clay, rushes (a type of plant), wicker, grass, bamboo, or tree bark when building. Stone was used for construction primarily in the northeast and east of Africa. Elsewhere in Africa, stone was rarely used for anything but altars in shrines, and then it tended to be used its natural form. The majority of Africans lived in huts. These were usually windowless, with the only opening being a doorway. As a result, interiors were smoky from the open cooking fires or clay ovens. Huts were most often circular but could be oval. Their walls were made of clay that had probably been dug up and transported by women. These clay walls were built up in circular layers, first a bottom one of perhaps eight inches high with an opening for the doorway. The next layer would then be spread on top of the first. Sometimes walls had frameworks of wattle, or poles intertwined with branches. The wattle would be covered inside and out with clay. In areas where clay was hard to find, walls were made of tree bark or woven rushes. Such walls seem to have been most often constructed in grassy areas that were drier than Africa’s rain forests. The herdsman culture of the Sahara grasslands of 5095-2780 B.C. built huts of wicker with grass roofs. Many materials used in ancient African building were not durable. Buildings disappeared quickly if they were not maintained. For instance, wood decayed rapidly in the moist regions of Africa, and in the drier regions voracious termites ate it away. Even clay bricks eroded from wind and rain. 39 The size, shape, and architecture of houses remain obscure. Apart from pieces of burnt clay with twig impressions found at various sites, possibly indicating some sort of light wooden framework supporting daub walls, and a number of postholes. 40

Women

Women in African tribes and chiefdoms were honored played a key role in society. Power traditionally was determined by the needs of the society as a whole, with little regard to gender. Position of power, according to van Niekerk, were accorded in the interest of collectively and women in power roles did not cause any tension or disharmony. Women and men enjoyed roughly equal social status in many tribes, the sexes in other societies were treated quite unequally. For example, the Maasai of Kenya did not allow women to own property, divorce, or make important decisions. Among the Touareg of the Sahara, for example, women choose their own husbands and sexual partners, in fact they took lovers when their husband were away. 41 They owned property and, in the case of divorce, get custody of the children.

Children

In Africa, the raising of children involves not only a child’s immediate family but also the community at large and the child’s ancestors. Child rearing also involved a reinforcement of the cultural values and traditions most cherished by each particular society. In most African societies, community rites surrounding child rearing started at birth. The most ancient traditions of the Kikuyu, for example, called for them to bury the placenta of a recently born child in an uncultivated field. This was done because, to these pastoral people, open pastures symbolize all that is new, fertile, and strong. The Yansi, on the other hand, traditionally threw the physical remnants of birth into the river as a way of showing that the child belongs to the community. Both practices were meant to ensure that healthy children were born in the future. Since the earliest times, Akan fathers, for example, traditionally were called upon to pour the child’s first libation, or tribute, to the ancestors. Akan fathers also were required to provide the child’s first pillow, which was a clean old cloth believed to carry the father’s spirit. Among many African peoples, names were traditionally a sign of a strong belief in reincarnation, and children received the names of those ancestors they most resembled in physical features or behavior. A child might also have received the names of grandparents or significant community leaders.

Breast-feeding, for many peoples, represented the most critical time for young children, and it generally lasted anywhere from 12 to 24 months. In other societies, the piercing of ears or the wearing of particular kinds of jewelry or charms indicated that children had become full members of society. Work tasks traditionally offered other learning experiences for young children. In some societies, especially in ancient times, children between two and four years old were expected to help with hunting and gathering, household tasks, herding sheep and goats, and feeding domesticated animals. As the children reached their middle years, more responsibilities were placed upon them, including obtaining water for the household, herding livestock, cultivating food, cooking, and running errands. By assisting adults, children expanded the food reserves of the family, providing for greater economic opportunities through trade or sale. 42

Children Initiation Rites

Children in many traditional African cultures underwent initiation rites upon reaching puberty. Ancient initiation rites are still practiced in traditional African societies. At that time initiation rites often entailed the removal of all children from a particular age group to a secret location. The children underwent various tests to prove their strength, and in some cases, injuries were inflicted to symbolize the change the child was expected to undergo. Some initiation rites even simulated death and rebirth. Perhaps the most important element of the initiation rite was the instruction in religion, sexuality, and appropriate behavior that the children undergo. This aspect of the ritual was intended to ensure that, when the initiates returned to the village as adults, they were able to be successful members of the community. 43

Slavery

Slavery in historical Africa was practiced in many different forms: Debt slavery, enslavement of war captives, military slavery, and criminal slavery. 44 Like many ancient cultures, the Ancient Africans often enslaved captives taken during successful military campaigns. Criminals were also enslaved as a punishment for their crimes. Slaves were sent to work in the dangerous mines, where they died in great numbers. Some were forced to fight in the army. Others became domestic servants to individual families; in many cases, slaves were attached to large estates, in much the same way medieval serfs belonged to the lord of the manor on which they lived. Female slaves were valued for skills in weaving and other domestic chores; some were sold as concubines. There was no racial component to enslavement of Africans by other Africans. Both the slave’s owner and the slaves typically were black, although they were often members of different tribal groups. 45

The types of slavery in Africa were firmly identified with family relationship structures. In numerous African communities, where land couldn't be possessed, subjugation of people was utilized as a way to build the impact on an individual and extend connections. 46 This made slaves a perpetual piece of a master's heredity and the offspring of slaves could turn out to be firmly associated with the bigger family ties. Offspring of slaves naturally introduced to families could be coordinated into the master's connection groups and ascend to conspicuous positions inside society, even to the level of chief in certain occasions. However, stigma often remained attached and there could be strict separations between slave members of a kinship group and those related to the master.

Food

Ancient Africans obtained food in several ways: they hunted, fished, gathered, scavenged, herded, and farmed. The earliest peoples were hunter gathers. Their diet included large and small game, birds, fish, mice, grass-hoppers, crabs, snails, mollusks, fruit, nuts, wild cereals, vegetables, fungi, and other plants. Even in ancient times, hunting and gathering only used a portion of peoples’ time, allowing opportunity for other activities, including social interaction and artistic expression. Some historians, therefore, believe that were it not for population growth, ancient peoples would not have taken up farming, since it represented a much more time-consuming activity. In fact, it has been said that hunger was the motivating force behind agriculture, migrations, revolutions, wars, and the establishment of dynasties.

When the ancient African population grew larger than food sources could support, people began to engage in agriculture. While the hunters-gatherers did consume some wild cereal, the advent of farming meant that a steady supply of grain was available and that a surplus could be amassed to provide food in lean times or as currency in trading necessities and other items. The people of Ethiopia domesticated noog, an oil plant, and teff, a tiny grain that was not found elsewhere in Africa. Many varieties of wheat and barley were cultivated in Ethiopia, where the altitude was conducive to their growth. The peoples of West Africa’s ‘yam belt’ cultivated many plants used in soups, including fluted pumpkins. The Igbo used Yams as a carbohydrate staple, rolling pounded yams into a ball and dipping them into a sauce before eating them. The people of marginal areas experimented with a fluctuating blend of farming, hunting and gathering, and fishing. Climate change also affected the diet. For example, gradual desiccation in the western Sudanic belt affected the development of cereals. Other Africans living in better-watered areas often farmed as well as herded livestock. They could thus combine both grown crops and livestock products in their diet. Those farmers living in the more heavily forested areas had smaller domesticated animals such as goats and fowl. The preparation and consumption of food was often associated with rites and rituals. For example, the peoples of the Maghrib ate communal meals built around couscous, which was made from pulverized grain. Women prayed aloud during the grinding process, and the communal consumption of the couscous was an expression of solidarity. Among the Igbo, the eating of yams was forbidden before the New Yam Festival. This was most likely done to allow the tubers to grow to maturity. 47

Wild Foods

Fat requirements were satisfied by the exploitation of oil palm (Elaeis guineensis) and incense tree (Canarium schweinfurthii), along with other oleagenous wild plants. Hunting and (seasonal) fishing undoubtedly also made important subsidiary contributions to the human diet, although direct evidence is hard to come by because of poor preservation conditions for bones. On the Atlantic coast, a pattern of economic specialization of settlements developed during the Early Iron Age, reflected by early occupation sites with shell middens. This coastal shell-midden economy was based on the procurement of estuarine and mangrove resources by fishing and gathering, supplemented by some marginal hunting; at low tide, shellfish were collected in the mangrove muds and from prop roots. 48

Agriculture

Ancient peoples in Western Africa began farming the oil from palm trees around 5000 B.C. The palm trees had many uses. Its wood and branches were used for building and its leaves for weaving into mats and baskets. Ancient Africans learned how to extract palm oil from the red fruit of the oil palm. The fruit was mashed and boiled in a large pot. The liquid was poured through a sieve to remove the mashed fruit, leaving palm oil in the water. The oil and water mix, was left to separate and the water poured off. Palm oil was used to fry food, and to make bread and candles. 49

Near Eastern agriculture traveled as far as the Ethiopian highlands but could not move farther into the continent, owing to geographical and climatic barriers. Hunter-gatherers in the area just south of the Sahara domesticated livestock starting about 3000 B.C. but did not begin growing crops for another thousand years or so. Between 2000 B.C. and 1 A.D. people living south of the Sahara developed several different kinds of crops, depending on climatic conditions; people in West Africa grew rice and yams, while people in the Sahel grew drought-resistant grains. Farming and herding did not travel south of the Serengeti until about 1 A.D. Eastern Africa around Kenya and Tanzania was home to the tsetse fly, which caused sleeping sickness, deadly to both humans and cattle. As cattle evolved resistance to the disease, farmers and herders began moving south into southeastern Africa, bringing African crops with them. People in this area gradually adopted some Asian crops as well, importing them from Indian traders. Africa’s geography presented a major obstacle to the spread of agriculture. Africa was a large continent with a wide range of climatic conditions. Its longest axis runs from north to south and crosses the equator, which means the various parts of Africa were very different from one another. The length of days varied depending on distance from the equator; this was important, because many plants grow well only in days of a particular length. The Sahara was another enormous impediment. Middle Eastern crops grew well in the Nile River valley, with its stable climate and regular flooding. They also grew well in other locations with climates similar to that of the Near East, such as the Ethiopian highlands. North Africa’s climate and geography was very different from those of sub-Saharan Africa. The main African grains were sorghum, pearl millet, and African rice. Africans also domesticated yams, oil palms, cowpeas, and groundnuts. Sorghum and pearl millet were domesticated in the dry areas of the Sahel. Rice and yams grew better in the wet regions of the forest-savanna border in West Africa. In Ethiopia people domesticated two unique grains, finger millet and teff. Sorghum was a grass grown for its grain. People made it into couscous (a grain like type of pasta) and porridge, which they ate with vegetables and sauces. The ancestor of African rice resembled the wild rice of Asia and was closely related to it. African rice was domesticated in West Africa near the Niger River around 200 A.D. Yams were tubers or roots that grew underground. People prepared them like potatoes, boiling or roasting the flesh. 50

Legal System

Most ancient Africans cultures did not have any written codes of law. Generally, the code of conduct was the clear and known to all members of the tribes. While some taboos in traditional tribal societies were equivalent to the crimes in modern Western society, such as murder, theft and rape, others, such as failure to respect parents and elders or lying, were not. Punishment in tribal societies were communal, someone who violated a taboo was likely to be ostracized or punished by the whole group. 51

Ancient African tribes consisted of interpersonal and group relations involving clans and associations. The family was the unit of the tribe but the form of family and much of a family’s behaviors were fashioned by the tribal culture. The cultural idea for each tribe throughout Africa was the Ma’at concept of having the right relations with and behaviors toward other people. From this ideal came a set of ‘designs’ for carrying on the life of the tribe. The stable theme around which these ‘designs’ were accountable to was the tribe’s religion. In other words, each tribe and its religion had a precise, one-to-one association and that association had its own unique way of viewing the same universe that other tribes saw. Throughout African history, the religion seldom had a component of retributive justice. Otherwise, all tribes had their own territory and most shared the same values and conventional customs. Some had a chief and some had tribal elders in the tribe’s top politico-social position. One example of common law control were secret societies, like the Poro fraternity of Liberia, which all men join when they came of age.

African Moots

Bickering, sniping and backbiting were common between close relatives as well as unacceptable behaviors were handled variously by Ancient Africans. Since early Africans societies were initially without chiefs, family or clan matters were settled by the family council, each having its own elder or by any mutually acceptable elder. Moots were the origin of the African common law. Moots and courts existed side by side. Moots dealt with the resolution of family disputes, mistreating a spouse, disagreements over inheritance, or failing to pay debts, and were held in homes of the complainant rather than in public places. All concerned parties would sit very close to one another in a random and mixed fashion. The investigation was more in the hands of the disputants themselves and without any attempt to blame one party. Because the relevance was very broad, the airing of grievances was more complete than in formal courts of law. The idea was to spread out fault in the dispute to both parties. The principle was to do what brought most harmony to the entire group and that was more important than solving the problem. This was most likely to happen by finding what everyone had in common rather than searching for differences. Thereafter, whatever matter remained unclear was not a problem. The objectives were to reintegrate the guilty party or parties back into the community, restore normal social relations between the disputing parties; and resolve any left-over bits of anger. The ending of the proceeding involved the ritual of an apology to the victim in order to symbolize agreement with the sanctions imposed by the moot. 52

Major Civilizations

The continent of Africa has been rich with the history of mankind. Some of the earliest archeological discoveries of human development have been found in Africa. This continent has seen the rise and fall of many great civilizations and empires throughout its history. Descriptions of the major ancient civilizations are given below:

East Africa

In East Africa, the rugged and difficult geography strongly influenced the development of its cultures, small and large. These cultures were also influenced by the nearness of the Egyptian Empire.

Those who sailed south from Egypt toward the upper Nile River had to overcome five great sets of rapids and falls called cataracts. At the sixth cataract stood Meroe and on a large island in the middle of the river. It was an elaborate city with monumental sculptures and small pyramid tombs, but it was not part of the Egyptian empire. By 600 B.C., the same time period as the height of the ancient Nok in West Africa, Meore was the capital of a rich, independent culture that adopted many Egyptian traditions. In fact, Meroe became so powerful that it briefly ruled Egypt. Burials of Meroe’s nobility included elaborate funeral offerings such as gold and alabaster items and human sacrifices. Seven queens were recorded in the monuments of Meroe. As powerful rulers, they were called Candace which meant queen or queen mother.

Meroe was best known as a center of iron making. Archaeologists believe that iron making skills spread from Meroe across the continent to the Nok people in Nigeria. The merchants of Meroe were also clever in developing their trade skills and adopted a form of hieroglyphic or picture writing for their records.

Meroe became the center of trade between the Mediterranean Sea and other parts of Africa. The city on the Nile may have traded with countries as far away as China. Meroe traded ivory and skillful ceramics for gold with West Africa over two thousand miles away. Eventually Meroe declined because of the growing power of nearby Aksum, which took over the rich trade routes that had bestowed such renown and riches on Meroe. 53

West Africa

Once the great desert began to form in the center of West Africa, many of the Saharan people moved south and lived either in the forests of the lower Niger River or in the grasslands of the upper Niger. Between 500 B.C. and A.D. 625, multiple kingdoms developed in the two regions with under developing governments, weak educational systems, religious customs and unorganized cities. They were little skillful in metal working, trade, agriculture and the arts.

The rich culture that rose in West Africa built on each other, each one advancing the knowledge and skills developed by the previous one. They also learned new ideas through elaborate trading networks linking them with each other and with groups outside their region. 54

Aksum

The people of Aksum descended from Arab farmers who had sailed across the Red Sea long ago, they developed a culture completely separate from the influence of Egypt. Around A.D. 300 Aksum conquered Meroe and took its place as the trade center of northeastern Africa. The trade was split three ways: between West Africa, the Mediterranean cultures, and the countries around the Indian Ocean. The active seaport of Adulis on the Red Sea was Aksum’s chief trade city. Aksum’s official language was Greek, since Aksum traded with regions conquered by Greece’s Alexander the Great. Aksum’s coins and historic monuments were inscribed with the Greek Language.

Early Aksumite leaders built impressive tall and slender stone monuments called stelae, many of which mark tomb sites. Inscriptions on the stelae tell of Auximite rulers and their history. The Arab people who built the Aksumite Empire were not Muslim, and when they developed trade with the Greek world, they became interested in Christianity. The kingdom of Aksum became officially Christian around A.D. 450. 55

Geography of Aksum

Archaeology shows the Aksumite kingdom as a tall rectangle roughly 300 kilometers long by 160 kilometers wide, lying between 13 degrees and 17 degrees north and 30 degrees and 40 degrees east. It extends from the region north of Keren to Alagui in the south, and from Adulis on the coast to the environs of Takkaze in the west. Addi-Dahno is practically the last-known site in this part, about 30 kilometers from Aksum. 56 Aksum was located on the northern edge of the Tigray Plateau at 7000 feet on the edge of an east-west depression reachable from the east via valleys from the Red Sea coast. From Aksum, there was also access to the west down into the Sudanese plains and beyond via the Takkaze Valley. The ancient water storage and irrigation dam systems around the city have been noted for its numerous springs. It lay about 100 miles inland and slightly southwest from the Red Sea port of Massawa and ancient Adulis, not far from the border with Eritrea. 57

Coins of Aksum

Aksumite coins were of special importance. It was through them alone that the names of eighteen kings of Aksum are now known. Several thousand coins have been found. The ploughed fields around Aksum throw up a good many, especially during the rainy season when the water washed away the soil. Most were of bronze, and they varied in size from 8 to 22 millimeters. They depicted kings, often showing the head and shoulders, sometimes with and sometimes without a crown. Only one was represented sitting on a throne, in profile. The coins carried various symbols. Those of the early kings (Endybis, Aphilas, Ousanas I, Wazeba, and Ezana) bore the disc and crescent. All coins made after Ezana's conversion to Christianity depict the cross, either in the middle of one side, or among the letters of the legend inscribed round the edge. In some cases, the bust of the king was framed by two bent ears of corn or one straight ear is represented in the center, as on the coins of Aphilas and Ezana. Perhaps the ears of corn were emblems of a power to ensure the fertility of the land.

The coins bore no dates, and this gives rise to many conjectures when it comes to classification. The oldest type - probably the one minted in the reign of Endybis - goes back no farther than the third century.

Language

The earliest alphabet used in Ethiopia was of a south Arabian type. It transcribed a language that was akin to the Semitic dialects of south Arabia. Aksumite writing differs from this south Arabian script but was nevertheless derived from it.

The first examples of Ethiopia script properly so-called date from the second century of our era. They were consonantal in form. The characters were still reminiscent of their south Arabian origin, but they gradually evolved their own distinctive shapes. The direction of the writing, which was initially variable, became fixed, and it then ran from left to right. These first inscriptions were engraved on tablets of schist. They were not numerous and comprised a few words only. The oldest was discovered at Matara, in Erythrea. An inscription engraved on a metal object has been found which dated from the 3rd century. It mentioned King Gadara and is the first Ethiopian inscription known to bear the name of Aksum. Other texts were engraved on stone. The great inscriptions of King Ezana belonged to the 4th century. It was with them that syllabism first appeared, soon becoming the rule in Ethiopian script. Vocalic signs became integrated into the consonantal system, denoting the different tone qualities of the spoken language.

This language, as revealed in the inscriptions, was known as Ge'ez. It was a member of the southern group of the Semitic family. It was the language of the Aksumites 58 and later on the Ethiopian Church. Ge'ez was a Semitic language of the Southern Peripheral group, to which also belong the South Arabic dialects and Amharic, one of the principal languages of Ethiopia. Both Ge'ez and the related languages of Ethiopia were written and read from left to right, in contrast to the other Semitic languages. 59

Political System

Aksum may have been initially a principality which in the course of time became the capital province of a feudal kingdom. History confronted its rulers with various tasks, the most urgent of which was the establishment of their power over the segmentary states of northern Ethiopia, and the assembling of these into one kingdom. Success depended upon the Aksumite ruler's strength and the degree to which it exceeded that of other princes of ancient Ethiopia. It sometimes happened that a new ruler, on ascending the throne, was obliged to inaugurate his reign with a countrywide campaign to enforce at least formal submission on the principalities. Although this action was taken by an Aksum monarch whose name has not survived, but who established the Monumentum Adulitanum, Ezana was obliged to assert his authority anew at the outset of his reign.

The founding of a kingdom served as the basis on which to build an empire. From the close of the 2nd century up to the beginning of the 4th, Aksum took part in the military and diplomatic struggle waged between the states of southern Arabia. Following this, the Aksumites subjugated the regions situated between the Tigre plateau and the valley of the Nile. In the 4th century they conquered the Meroe kingdom, which by that time had declined. In this way, was built an empire extending over the rich cultivated lands of northern Ethiopia, Sudan and southern Arabia, which included all the peoples who inhabited the countries south of the boundaries of the Roman empire, between the Sahara to the west and the inner Arabian desert of Rub'el Hali to the east.

The state was divided into Aksum proper and its vassal kingdoms, the rulers of which were subjects of the Aksum king of kings, to whom they paid tribute. The Greeks called the Aksumite potentate the basileus (only Athanasius the Great and Philostorgius termed him tyrant); the vassal kings were known as archontes, tyrants and ethnarchs. Some authors such as John of Ephesus, Simeon of Beth-Arsam and the author of the 'Book of the Himyarites', accorded the title of king (mlk) to the Aksumite 'king of kings' and also to the kings of Himyar and 'Aiwa, who were his subjects. But the Aksumite term for all these was 'negus'. Apart from leading armies in time of war, these neguses assumed command of building operations.

Apparently, court officials carried out the functions of government, serving, for instance, as envoys. The Hellenized Syrians, Aedesius and Frumentius, who had been made royal slaves, were later promoted, one to the office of wine-pourer, the other to the position of secretary and treasurer to the Aksum king. 60

Economy and Industry

In between the social elite and the laboring mass there was a whole range of craftsmen and specialist workers. Aksumite material culture was sophisticated and diverse, which demonstrated the existence of a wide variety of skills and substantial technological knowledge. Stone was quarried, transported in large pieces, carved, erected as stelae, used extensively in building, and sometimes inscribed. Water-storage dams were constructed, as well as terracing and irrigation systems. The manufacture and use of fired bricks and lime mortar were understood, and how to employ these materials in brick arches and brick barrel-vaulting. Large quantities of pottery were made, without the use of a potters wheel but nevertheless often of high quality. Metallurgical expertise included the working of gold, silver, copper and bronze, and iron. An impressive range of relevant processes was understood, including smelting, forging, welding, riveting, production of plate, drilling, perforating, casting, polishing, plating (both annealing and mercury-gilding), enameling, and the striking of coins. Ivory was carved and lathe-turned with great skill, leather was worked and probably textiles were manufactured. Wine was made from grapes and glass-working was carried out, most likely using imported glass as the raw material.

During the first century A.D., Adulis and the capital Aksum became some of the most important port cities in Africa. Because of the efficient trade network with India, Arabia, Persia, the Mediterranean region and the interior of Africa, Aksum grew very wealthy. Aksum's location allowed it to access to the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea. Many items including slaves were traded with textiles and glassware. Since Aksum thrived in trade, Aksum merchants thought it would be helpful to mint coins, they were also the first African Kingdom to do so. Geography helped Aksum flourish through one of the most important regions in Africa, and the land was also very fertile for agriculture.

The kings also placed taxes outside the city on trade to collect from passing merchants. Tribute was collected from neighboring rulers inside the city to help sustain the government and the twenty thousand population. But the main source of wealth all came down to trade, ‘geography is destiny’.

Import and Export

Imports, indeed, made a substantial contribution to Aksumite life, particularly to that of the wealthier. As already explained, the location of Aksum and its kingdom enabled it to tap a range of raw materials from deep within the African continent. However, that same location also allowed it to participate in the maritime trade of the Red Sea which, significantly, was flourishing at the very time that Aksum was so successful. The Aksumite port of Adulis, only eight days journey from Aksum itself, became the gateway through which a stream of imports and exports passed. In particular, the late classical world of the Mediterranean was hungry for the exotic products of the African interior, and the Aksumites in turn seem to have developed a remarkable appetite for the sophisticated manufactures of that world. Using both archaeological and historical sources, it is possible to reconstruct the list of exports and imports. Going out were ivory, gold, obsidian, emeralds, aromatic substances, rhinoceroses’ horn, hippopotamus teeth and hide, tortoiseshell, slaves, and monkeys and other live animals. Coming in were iron and other metals, and things made of them, glass and ceramic items, fabrics and clothing, wine and sugar-cane, vegetable oils, aromatic substances and spices. As was so often to be the case with African external trade, this was basically one involving an exchange of raw materials and primary products for manufactures and value-added commodities.

This participation in what was one of the major world trade routes, reaching from the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean, greatly increased Aksum’s wealth. With wealth came power, so that Aksumite political authority at times extended across the Red Sea to the Yemeni highlands and perhaps westwards as far as the Nile Valley. It was, it seems, that the increasing importance of Aksum’s role as a supplier to the outside world of African commodities that contributed to the decline of Meroe, as trade moved away from the Nile Valley to the Red Sea. The extent of Aksumite overseas contacts is indeed impressive, as indicated by Aksumite gold coins found in Yemen and India and by Indian coins found in north-east Ethiopia. 61

Ethiopia

Ancient Ethiopia also known as Abyssinia, was indeed a separate country whose emperors declared themselves as the descendants from Solomon  and Queen of Sheba mentioned in the Old Testament. Their conversion to Christianity was said to be affected through the medium of that nobleman who served a queen of the same name (a name that, like that of the Pharaohs and Ptolemies of Egypt, was inherent to royalty). In addition to this nobleman’s labors, it was also certain that the Christian church of Abyssinia was indebted to St. Athanasius, who instructed the Abyssinians in the principles of Christianity, and placed them under the Patriarch of Alexandria as their head. 62

and Queen of Sheba mentioned in the Old Testament. Their conversion to Christianity was said to be affected through the medium of that nobleman who served a queen of the same name (a name that, like that of the Pharaohs and Ptolemies of Egypt, was inherent to royalty). In addition to this nobleman’s labors, it was also certain that the Christian church of Abyssinia was indebted to St. Athanasius, who instructed the Abyssinians in the principles of Christianity, and placed them under the Patriarch of Alexandria as their head. 62

Geography

Abyssinia, extended from the 6th to the 15th degree of north latitude, and was situated to the south of Nubia, therefore, unique among the countries of the African continent. It has been compared, indeed, to a vast fortress, towering above the plains of eastern Africa. It is, in fact, a huge, granitic, basaltic mass, forming a great mountainous oval, with its main ridge toward the east. A chain ran for over 650 miles from north to south; seen from the shores of the Red Sea, it looks like a vast wall, some 8,000 feet high near Kasen, opposite Massowah; over 10,300 at Mount Souwaira; 11,000 at the plateau of Angolala, and more than 10,000 in Shoa.

Ethnology

Few eastern or African nations exhibited such various aspects as the aborigines. Descendants of Cush were locally known as Agas, or ‘Freemen’, and still formed the basis of the Abyssinian nation. On the west, they intermarried with the ancient Berbers, and with the blacks of the Soudan, who must not be confused with the Niger, Congo, and Zambesi tribes. On the east, Semitic peoples, Arabs and Himyarites, having crossed the Red Sea in the 4th century B.C., conquered the whole eastern coast of Africa, and settled chiefly in the province called, after them, Amhara. 63

Sudan

Sudan, country located in northeastern Africa. The name Sudan derives from the Arabic expression bilad al-sudan (‘land of the blacks’), by which medieval Arab geographers referred to the settled African countries that began at the southern edge of the Sahara. For more than a century, Sudan—first as a colonial holding, then as an independent country—included its neighbor South Sudan, home to many sub-Saharan African ethnic groups. 64

During the 5th millennium B.C. migrations from the drying Sahara brought neolithic people into the Nile Valley along with agriculture. The population that resulted from this cultural and genetic mixing developed social hierarchy over the next centuries become the Kingdom of Kush (with the capital at Kerma) at 1700 B.C. Anthropological and archaeological research indicate that during the predynastic period Nubia and Nagadan Upper Egypt were ethnically, and culturally nearly identical, and thus, simultaneously evolved systems of pharaonic kingship by 3300 B.C. 65

Northern Sudan's earliest historical record comes from ancient Egyptian sources, which described the land upstream as Kush, or ‘wretched.’ For more than two thousand years the Old Kingdom of Egypt (c.2700–2180 B.C.), had a dominating and significant influence over its southern neighbor, and even afterward, the legacy of Egyptian cultural and religious introductions remained important.

Over the centuries, trade developed. Egyptian caravans carried grain to Kush and returned to Aswan with ivory, incense, hides, and carnelian (a stone prized both as jewelry and for arrowheads) for shipment downriver. Around 1720 B.C., Canaanite nomads called the Hyksos took over Egypt, ended the Middle Kingdom, severed links with Kush, and destroyed the forts along the Nile River which were established by Egyptians to guard the flow of gold from mines in Wawat, the area between the First and Second Cataracts. To fill the vacuum left by the Egyptian withdrawal, a culturally distinct indigenous Kushite kingdom emerged at al-Karmah, near present-day Dongola. After Egyptian power revived in 1570 B.C., and Egypt had established political and military mastery over Kush, officials, priests, merchants and artisans settled in the region. The Egyptian language became widely used in everyday activities. Many rich Kushites took to worshipping Egyptian gods and built temples for them. The temples remained centers of official religious worship until the coming of Christianity to the region during the 6th century. 66

Nigeria

The Late Stone Age, between roughly 10,000 B.C. and 2000 B.C., was a period of major firsts for human development in the territories in and around modern-day Nigeria. The first known human remains in this region were found in the Iwo Eleru rock shelter in what is now southwestern Nigeria, and have been dated to around 9000 B.C. Agriculture was developed in Nigeria in between 4000 and 1000 B.C. and the development of agriculture allowed for the establishment of more permanent settlements – that is, villages and village groups. Agriculture meant a move away from hunting and gathering activities, and the centralization of food resources allowed people to congregate in larger numbers on a permanent basis. 67

The earliest states in the territories encompassing modern-day Nigeria were most certainly of a very small-scale, decentralized nature. Political structures in these societies were so fragmented that earlier generations of scholars referred to them as stateless societies. Such a characterization was misleading. True statelessness implies a lack of political authority and, therefore, the existence of anarchy, which none of these societies exhibited. A better characterization of these societies’ political organization was decentralized, in that political hierarchy rarely reached higher than the village or village-group level, even though the overarching cultural identity could incorporate many different village groups. All Nigerian societies originally functioned as decentralized states; many societies in the middle-belt region and the southeastern part of modern-day Nigeria maintained their decentralized state structures long after the development of strong, centralized states in other parts of the region. 68

Political power in Igbo society tended to be founded on an age-based hierarchy at the village level: that is, elders, defined as the heads of patrilineal lines, were responsible for the most important decisions of a community. Multiple villages were centered on a market, which also served as a forum for village-group meetings. At the village level, all members of the community could speak their mind about village affairs, while, at the village-group level, members of secret societies tended to represent the interests of their respective villages. Decisions at the village group level were not binding, however, as any individual village could choose whether or not to follow the guidelines of village-group councils; they could not be forced into submission. Each village-group system functioned autonomously; nevertheless, all village groups were considered Igbo, based on a common language, similar religious beliefs, and various inter-group social institutions, such as intermarriage, membership in secret societies, and common oracle worship. Similar institutions existed in other decentralized societies, such as those of the Isoko, Urhobo, and Ibibio in the southeast and the Tiv of the middle belt. Such structures probably formed the basis of state formation in all societies in the region at different times throughout the first millennium A.D. 69

The primary economic activity of the Igbo during the Iron Age was cultivation of yams (ji) and cocoyams (ede), which constituted their staple. The cultivation of both crops helped in shaping their work ethic and competitive spirit. In addition, it intensified social stratification and the division of labor amongst them. Traditionally, yams were seen as ‘men’s crops’ and ‘the king of all crops’ because of the dominant role they played in the diet of the people. Unlike other seasonal crops, yam tubers can be stored and eaten all year round. Yam tubers became particularly important after the planting season (March–June), a period of scarcity, when they were used to stave off famine (unwu). 70 Like the men, women played key roles in the traditional Igbo agrarian economy. For example, they helped their husbands in carrying the yam tubers to the farms and in planting them in the mounds. Women were also responsible for weeding the farms with their hoes (ogu) to ensure that they would not be overgrown with weeds. More importantly, they planted crops that exclusively belonged to them, called “women’s crops,” including okra (Abelmochus esculenta), which was probably domesticated in Igboland; pepper; melon (Colocynthis vulgar; Igbo, egusi); and the three-leaved yam (onu). 71

Local and regional trade was conducted in the sacred politico-religious and commercial center of a senior village headed by its priestly-chief of the earth-goddess (Ezeala). Some of the ancient markets in parts of Igboland were called “ahia muo ala” (markets of the earth-goddess) because of the close association between them and the goddess. The markets were held during the weekly propitiation ceremony of Ala, a major religious festival involving the entire community. The market day was, therefore, seen as a holy day. 72

Family Structure

Nigeria was often referred to as the ‘Giant of Africa’, owing to its large population and economy. The country was viewed as a multinational state as it had inhabited by 250 ethnic groups, of which the three largest were the Igbo, Hausa and Yoruba; these ethnic groups used to speak over 250 different languages and were identified with a wide variety of cultures. If we only see Igbo of Nigeria to understand the family system, law and legal system of different parts of Nigeria, so it had a patrilineal system of. The Igbo lived in villages in which all or nearly all the people were related through their fathers. Their society was also patrilocal, which meant that when a woman married, she left her parents’ village and moved into her husband’s.

The importance of extended family was reflected in kinship terms. The same term, nna, for example, was used to refer to a person’s father and uncles; nne refers to both mothers and aunts. The terms for brother and sister (nwa nne/nwa nna, respectively) refer to cousins as well as siblings. Thus, an individual had many mothers and fathers - because it was normal for these people to copulate with numerous people and the fathers of these children were not known - and many siblings, emphasizing the importance of community and relationship. 73

Development of Sacred Laws

The cosmology of the Southern Igbo differentiated between three sacred spaces of power: The first one comprised of the sky (elu-igwe), the abode of the high god (Chukwu); the god of rain, lightening, and thunder (Kamanu); and other major divinities. Humans were located in the second space (uwa, ala) and so were deities subordinate to Chukwu, such as the earth goddess, nature spirits, and the minor divinities. In addition, evil spirits were located in the same space, although they were not worshipped. The third space, the world of the spirits (ala muo), was occupied by the ancestors, one’s personal god (chi), and demons.

But the three spaces were interconnected. Although Chukwu was the head of the Igbo pantheon, he was believed to have created a perfect world in his own image. The Igbo, then, distinguished between the ‘perfect or ideal world’ and the human world spoilt by the violations of the taboos of ‘Ala’ and ancestral laws, which were believed to be causes of sudden death, famine, drought, and other calamities.

It is important to distinguish between two levels of ancient Igbo political communities where the gods and their human agents or sacred authority holders exercised politico-religious authority: the kinship/lineage group level and the territorial/mini state level. At the kinship level, the Okpara, who held its ancestral staff of office (Ofo), was the dominant authority holder of his lineage group. His kinsmen often called him ‘onye nwe ezi’ (the owner of the compound). The Okpara and his kinsmen offered sacrifices to their ancestors (Ndiche) and Njoku (the yam deity) at their common meeting place (ovu) before new yams were harvested. He also ensured that ritual offerings were made to Ala-ezi, the moral force of the compound, and to Kamanu, located at the entrance of the compound to protect its members from sinister forces and evil people. The Ezeala was the head of his community at the mini state level. He held the ancestral staff of office of the progenitors of the mini state (Ofo Ala) and was called ‘onye nwe ala’ (the owner of the land) due to the ritual rights he exercised over the entire land in his community. The Ezeala was responsible for the weekly propitiation ceremony of Ala during their market day (ize muo) as well as for ritual offerings to the Njoku and Kamanu shrines located around the shrine of Ala. Similarly, he presided over the annual communal worship of the goddess, attended by the Okpara, Ezeji titled men, and other members of the community. In addition, he plucked a palm frond each month, using them to fix the dates of major cultural events in the annual lunar calendar of his community. 74

Legal System

In ancient Nigeria, the Okpara and the Ezeala’s respective symbols, Ofo and Ofo Ala, conferred legislative and judicial powers on them. Thus, for example, the Okpara and his compound and family heads had the right to make laws on marriage, birth, and death ceremonies of their kinsmen. They also arbitrated disputes stemming from feuds, inheritance, and succession. Similarly, the Ezeala presided over the meetings of the village council (Amala, derived from Ama-ala, meaning: abode of Ala, and the meeting place of the community), held at its common politico-religious and commercial center. The meetings of Amala were attended by the Okpara, Ezeji titled men, the Dibia (medicine men and diviners), and all adult male members of the community. They settled disputes and made laws, but important laws considered necessary for the survival of the community were ratified with Ofo Ala, giving them sacerdotal sanctions.

A violation of the sacred laws of Ala constituted an act of abomination (iru ala, alu) that upset the ritual equilibrium of the community. The offender was then held liable and responsible for his crime to avoid arousing the wrath of the earth-goddess. Chinua Achebe’s illustrates the severe punishment meted out against Okonkwo for violating the taboos of Ala by killing a kinsman accidentally during a burial ceremony. His compound and yams were destroyed, and he had to go into exile with his family members for seven years. But the laws of Ala were made not only for humans; they encompassed animals and other forms of life that thrive on earth. 75

Northern Horn of Ancient Africa

The northern Horn of Africa has long formed a distinct cultural area, despite being currently divided by a political frontier that is both disputed and increasingly impermeable. One of its defining characteristics was its separateness, and this is partly due to its physical diversity. The region comprised highlands that were bounded on the east by the precipitous escarpment bordering the Danakil lowlands and the Red Sea. To the west, the country descends more gradually to the extensive plains of the Nile Valley but is riven by the rugged valleys of the Takezze and other Nile tributaries. In the north, with decreasing altitude, the terrain became progressively more arid as the Sudanese lowlands converge with the Red-Sea coast. It was only to the south that the highlands continued, linking them with the principal mass of the Ethiopian plateau, near the western edge of which lies Lake Tana and the source of the Blue Nile. The greater part of the northern plateau was tilted down towards the west and drains to the Nile, resulting in a network of deeply eroded valleys that still form major impediments to inter-regional communication. 76

Most inhabitants of this land have long supported themselves by farming, being both cultivators of crops and herders of livestock, foraging for wild resources whether animal or vegetable – being of progressively decreasing significance. It is likely, however, that minority peoples of diverse economy – herders and, perhaps, hunter-gatherers – were also present throughout the period here considered. The different languages that were spoken all belonged to the extensive family known as Afroasiatic. 77

The continent of Ancient Africa was home to several civilizations. These civilizations were independent and had their own culture, legal, religious, social and economic systems, but only a few of these civilizations were able to survive overtime and their sacred traditions became lost in the whirlpool of history. The core reason for this destruction and disappearance was not due to lack of technological resources, but due to the fact that their systems were based on mundane thought and satanic rituals including polytheism, wrong believes about false gods, free sex, slavery, exploitation of weak etc. like the other ancient civilizations which were the super powers of their time. The fact is that systems which were based on the divine truth have existed through centuries despite the efforts of the barbaric people of various religions to demolish them. Since the ancient African civilizations also consisted of tyrannical and unjust systems, it was not able to survive and most were wiped out with the passage of time, and those which do remain, only exist in rudimentary form.

- 1 Jamie Stokes (2009), Encyclopedia of the People of Africa and Middle East, Fact and Files Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 218.

- 2 Ancient History Encyclopedia (Online Version): https://www.ancient.eu/Queen_of_Sheba/: Retrieved: 06-04-2019.

- 3 Jamie Stokes (2009), Encyclopedia of the People of Africa and Middle East, Fact and Files Inc., New York, USA., Pg. 218.

- 4 Aloysius M. Lugira (2009), African Traditional Religion, Chelsea House Publication, New York, USA, Pg. 13.

- 5 Mrs. Hofland (1826), Africa Described in its Ancient and Present State, A & R. Spottiswoode, London, U.K., Pg. 37-38.